L.A. area food centers are all that stand between thousands and hunger

One in six people in Los Angeles have no idea where their next meal is coming from. However, only so much can be done to combat the underlying problems: homelessness and unemployment.

Thousands of people in Los Angeles do not know where their next meal is coming from. The L.A. Food Bank helps provide food daily. It also hosted a Thanksgiving dinner on Nov. 26.

Thousands of people in Los Angeles do not know where their next meal is coming from. The L.A. Food Bank helps provide food daily. It also hosted a Thanksgiving dinner on Nov. 26.

Maria Hernandez has 11 children. Her youngest daughter is only one year old. She is unemployed. Her husband, recently let go from his job at a garment factory, collects and sells recyclables—plastic bottles, wooden pallets, among other things—so they can feed their children.

Hernandez, like thousands of food insecure people in California, relies on CalFresh, the current food stamp program. However, last November, the CalFresh program was cut, affecting over 4.1 million people, or 11 percent of the state’s population, according to Feeding America.

In order to handle the cuts, some of Hernandez’s children receive breakfast and lunch at school, along with about forty percent of low-income students who participate in school breakfast programs across Los Angeles, according to the California Food Policy Advocates.

Otherwise, Hernandez relies on food pantries and food banks around Los Angeles.

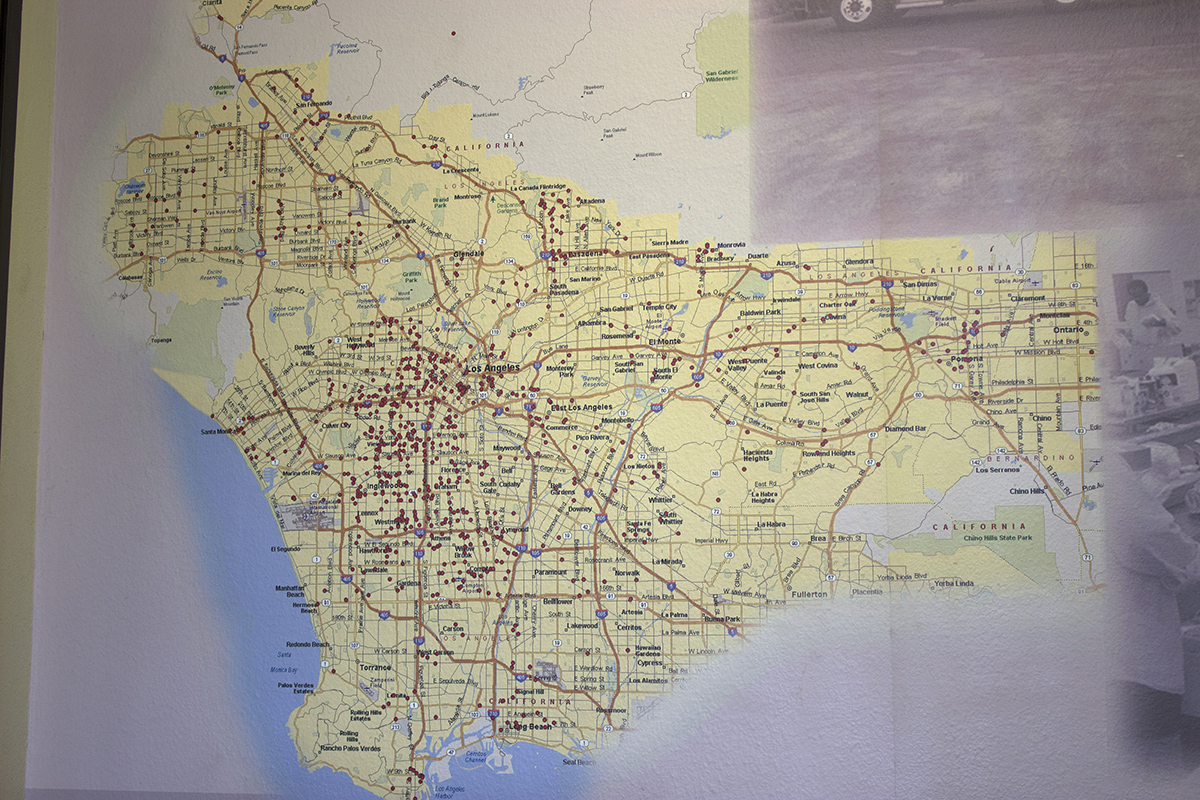

Hernandez is not alone. According to the Los Angeles Regional Food Bank, one in six people in Los Angeles County experience hunger and millions are food insecure. Food insecurity means a person does not know where their next meal is going to come from. As the largest county in the country, millions of people are unsure about when they will eat next and they are turning to non-profits for help.

“Hunger really is your neighbor, your friend, you family member, your colleague,” said Eli Lipmen, director of marketing and communication at the Los Angeles Regional Food Bank. “It is really just right across the street, it’s not far off in another part of the county or the country.”

Key Causes: Homelessness and Unemployment

Though there are many reasons why hunger is so rampant in California, the two main causes are the high rates of unemployment and homelessness.

“When people think of hunger they think of somewhere in the developing world where maybe there’s a famine or a war going on,” said Frank Tamborello, the director of Hunger Action L.A. “We got plenty of food in the United States, but people need income.”

According to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, the unemployment rate in Los Angeles County in October was 7.9 percent. Meanwhile, it is estimated that 57,737 people were homeless in Los Angeles in 2013. The Los Angeles Times reported in July that the Los Angeles homeless population is the second largest in the nation and makes up nine percent of the nation’s total.

Los Angeles is one of the few counties where restaurants can accept food stamps for CalFresh benefits but South L.A. and East L.A. are hungry neighborhoods, Tamborello explained. The areas are known as food deserts. That means it is hard to find and buy affordable or good-quality fresh food.

“Parts of South L.A. are known as food swamps because there is a lot of fast food clustered in those areas,” Tamborello continued. “So it’s kind of a dual problem because if you don’t have access to good food, you will eat whatever is cheap and starchy and available.”

Non-profits around Los Angeles work to face these issues while also feeding the hungry.

Acting on Hunger

Hunger Action L.A. focuses on education and advocacy. They hope to make policy changes that will help thousands, but they also have programs that help provide healthy food directly to the hungry. Tamborello says that donating food or feeding the hungry isn’t enough.

“We have to start looking at the whole picture to see where we can start making improvements,” he said.

Made up of only three full-time staff members, Hunger Action creates a 72-page booklet that has everything you need to know about how to access food programs in Los Angeles. The organization also helps people understand CalFresh and was there to support people when the program was cut last year.

The money for CalFresh is given on a plastic debit card. At 16 farmer’s markets in L.A., a person can use the CalFresh card and Hunger Action L.A. will give that person up to $10 extra dollars for that day.

“There is a whole patchwork of government programs, each one seems to run into a wall of insufficiency or overlap,” said Tamborello. For example, the SSI program, which helps the blind, elderly and disabled, has been cut by about 77 dollars a month — that’s someone’s groceries or the difference between getting evicted or not, said Tamborello. Tamorello and Hunger Action hope to help people work through these government pitfalls.

Sixty Million Pounds of Food

While Hunger Action focused on policy, there are other organizations that work with millions of pounds food for the hungry. One of those place is the Food Bank. Started in 1973, the L.A. Regional Food Bank served over 400,000 children and 22,000 seniors in the past year. They have 33,000 volunteers annually.

“For me, food and hunger is such an overwhelming issue when you look at the numbers and the need but we really address it in an overwhelming way,” said Lipmen. “And that’s the only way you can do it.”

The Food Bank works with over 680 agencies that pick up the food and distribute to the needy. It has gained 40 new agencies in just two years and has a waiting list of 1,000 due to the high demand for food access.

The most desired products, said Lipmen, are fresh fruits and vegetables, milk and dairy products and meat products. Two percent of donations are also non-food items such as children’s toys, toilet paper and detergent.

Each room at the Food Bank is littered with banana boxes, which are used because they have handles and a metal structure that remains intact. The Food Bank has a fleet of over 20 trucks and the freezer alone can hold 10 truckloads of food. They run on a budget of about $17 million, but when the product donations are calculated in, the budget ends up being about $75 million.

The Food Bank serves over 100,000 people weekly, while over a million pounds of food comes out of the facility per week.

Real Solutions to South L.A.

One of the 680 agencies on the Food Bank’s list is All People’s, which has been in the community for 77 years. Besides the food program, All People’s also provides parenting classes, therapy and counseling, support groups for women who are victims of domestic abuse and education services.

The main goal is for community members to have a comfortable place to go.

“Even if we don’t have the services they need, we’ll help them get those services, we’ll help them get whatever it is that they need,” said Julio Ramos, All People’s administrative director and director of social services. “I think that’s what makes us unique.”

All People’s is a place for people to connect and support each other. The playground outside is full of children giggling and running around—Ramos said that people use it on weekends for birthday parties. The employees are called by their first names and everyone is greeted with a smile or a hug.

Every year, All People’s hosts a Thanksgiving dinner. This year, on November 26, about 1,400 people came out to eat.

Leticia Ortiz-Gonzales, All People’s project coordinator, said her favorite part was “how grateful the people are, how much they enjoy it.” She said that people always ask if they’re hosting the event again, which is in it’s fifth year.

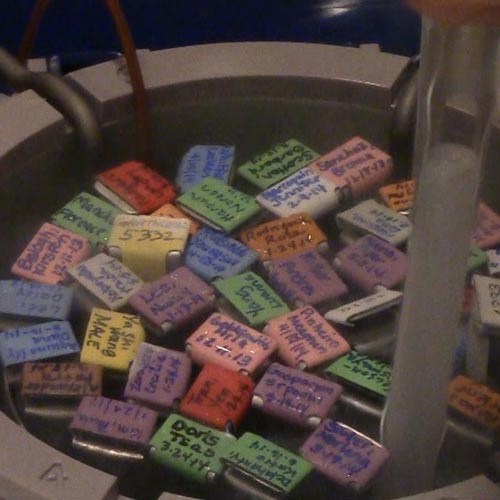

Many of the attendees use All People’s programs, such as the food program, regularly. The food program has about 1,400 families registered, with the average family containing three children. The families get 20-25 pounds of food per month.

Hernandez says that without the food program, she would not be able to feed her children a solid three meals a day. She is able to supplement the food she can afford.

She wants her children to have healthy choices. She loves combining fresh vegetables. Her one-year-old daughter loves steamed vegetables, especially carrots, potatoes and squash. Without the food program, she wouldn’t be able to give her children any healthy options.

“We always make it work,” said Hernandez, smiling softly.

No Solution to the Problem

However, policies are hard to change and some people will also fight against government programs that feed the homeless.

To fix the hunger issue, Los Angeles needs to address the big structural issues at hand, said Tamborello. Giving food donations to the homeless and hungry will not solve anything.

“The fact is with 300 million people, private charity is just not sufficient,” he said. “You can’t have a country with just a few strong, wealthy people and then masses and masses of people who are desperate for any kind of work or other kind of income that they can get.”